Learning the Backward Pass of FlashAttention

Part I Derivations

Scaling Transformers to longer sequence lengths has long been hindered by the computational bottleneck of self-attention, whose runtime and memory complexity scale quadratically with sequence length. FlashAttention and its subsequent versions

While there are many excellent tutorials available online that provide an in-depth introduction to FlashAttention, such as the YouTube video by Umar Jamil, the backward pass remains relatively underexplored. For someone like me, who has grown accustomed to relying on automatic differentiation (AD) engines embedded in modern scientific computing frameworks like PyTorch, JAX, and Julia to handle derivatives, understanding the backward pass of FlashAttention can be a bit daunting.

In this blog, I aim to give a detailed explanation about the backward pass of FlashAttention, breaking it down into two parts. In the first part, I will derive the relevant gradients using matrix calculus and validate the results using two alternative methods to highlight the elegance of matrix calculus. In the second part, we will walk through the Triton implementation of the backward pass to strengthen our understanding.

Revisiting Derivatives

Recall from single variable calculus, a real-valued function \(f\) defined in a neighbourhood of \(a \in \mathbb{R}\) is said to be differentiable at \(a\) if the limit

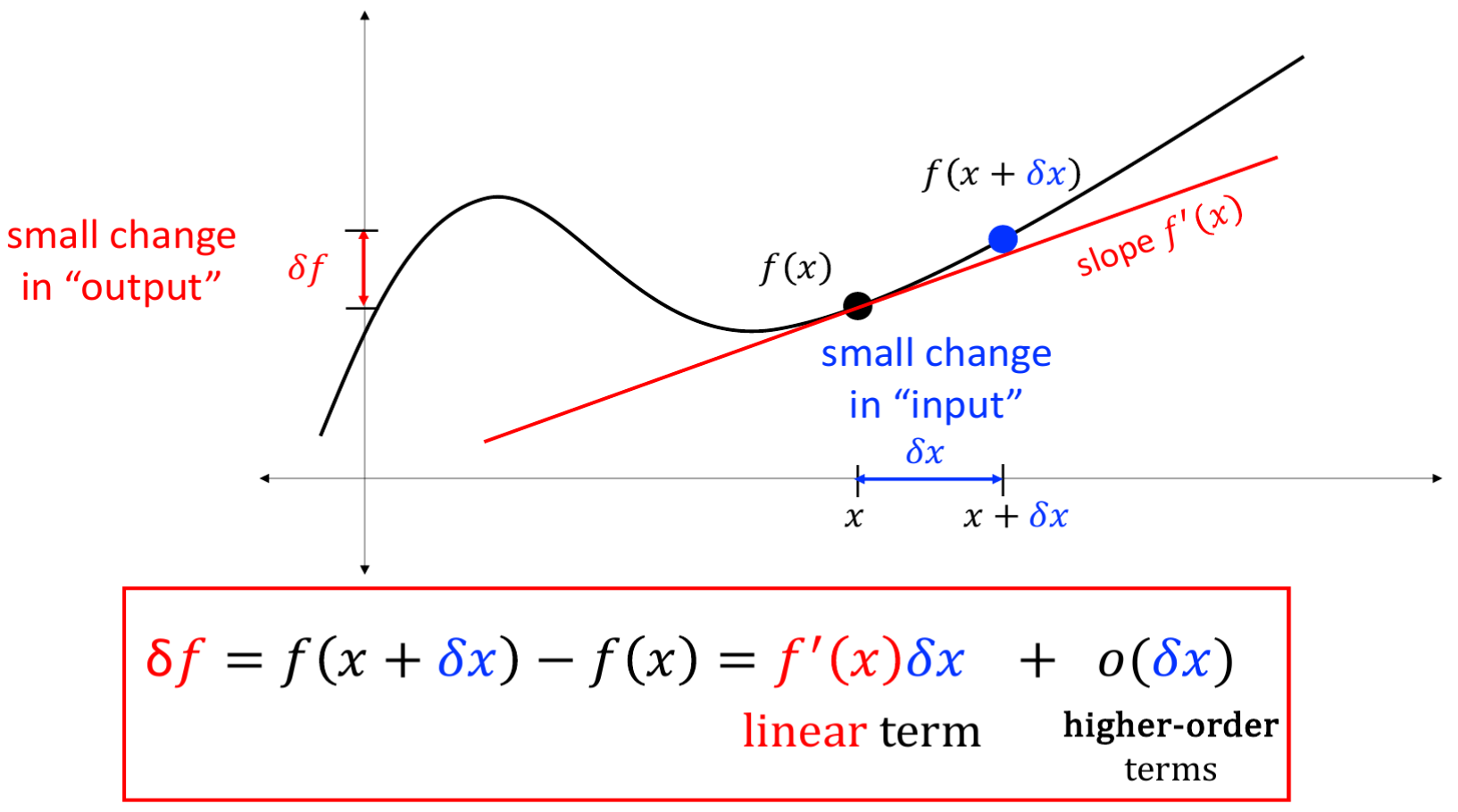

\[f^{\prime}(a) = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(a+h) - f(a)}{h}\]exists in \(\mathbb{R}\). However, such an expression does not easily lend itself to a more generalised definition of derivatives beyond scalar inputs, such as vectors, matrices, or functions. A more useful and fundamental way to view derivatives is the linear approximation of functions near a small neighbourhood of input values: \(\delta f = f(x + \delta x) - f(x) = f^{\prime}(x)\delta x + o(\delta x)\), or the differential form: \(df = f(x + dx) - f(x) = f^{\prime}(x)dx\). For example, let \(f : U \to \mathbb{R}\), where \(U \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n\) is open, i.e., a scalar-valued function which takes in a (column) vector \(x \in \mathbb{R}^n\) and produces a scalar in \(\mathbb{R}\). From college calculus, we know that \(df = \underbrace{\nabla f(x)^T}_{f^\prime(x)} dx\).

More generally, by the Riesz Representation Theorem

For the vector space consisting of matrices \(A \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}\), the default inner product is defined as \(\operatorname{Tr}(A^T B) = \operatorname{vec}(A)^T \operatorname{vec}(B) = \sum_{i, j}A_{ij}B_{ij}\), which is referred to as the Frobenius inner product, in order to make it a valid Hilbert space. Therefore, for a scalar-valued function that takes in matrices \(f(A)\), its derivative can be expressed as \(df = \operatorname{Tr}(f^\prime(A)^T dA)\).

Next, we will leverage this trick from matrix calculus to derive the formulas for the backpropagation of standard attention.

Deriving Gradients of Standard Attention

By Matrix Calculus

Given input sequences \(Q,\: K,\: V,\: \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times d}\) where \(N\) is the sequence length and \(d\) is the head dimension, the standard attention output \(O \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times d}\) is calculated as follows (forward pass):

\[S=QK^T \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times N}\quad P = \operatorname{softmax}(S) \quad O=PV \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times d}\]where \(\operatorname{softmax}\) is applied row-wise.

Then, assuming a scalar-valued loss function \(L\), by the backpropagation (i.e., reverse mode of automatic differentiation (AD)), the gradients of \(L\) w.r.t various inputs are calculated as follows:

\[\frac{\partial L}{\partial V} = P^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times d}\] \[\frac{\partial L}{\partial P} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} V^T \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times N}\] \[\frac{\partial L}{\partial S} = \operatorname{dsoftmax}(\frac{\partial L}{\partial P}) \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times N}\] \[\frac{\partial L}{\partial Q} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial S}K \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times d}\] \[\frac{\partial L}{\partial K} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial S}^T Q \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times d}\]First, we calculate the gradient w.r.t. \(V\) (\(\frac{\partial L}{\partial V} = P^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times d}\))

Fix \(P\) and vary \(V\). From above, \(dO = P(V + dV) - PV = P dV\). The differential of \(dL\) becomes:

\[dL = \text{Tr} \left( \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \right)^T dO \right) = \text{Tr} \left( \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \right)^T (P dV) \right).\]Substitute \(dO = P dV\):

\[dL = \text{Tr} \left( \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \right)^T P dV \right) = \text{Tr} \left( \underbrace{\left( P^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \right)^T}_{\frac{\partial L}{\partial V}} dV \right)\]Therefore, we get \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial V} = P^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times d}\).

Similarly, the gradient w.r.t \(P\) (\(\frac{\partial L}{\partial P} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} V^T \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times N}\)) is derived as, given \(dO = (P + dP)V - PV = dP V\):

\[dL = \text{Tr} \left( \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \right)^T dO \right) = \text{Tr} \left( \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \right)^T dP V \right) = \text{Tr} \left( V \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \right)^T dP \right) = \text{Tr} \left( \underbrace{\left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} V^T \right)^T}_{\frac{\partial L}{\partial P}} dP \right)\]where the cyclic property of trace is applied \(\operatorname{Tr}(ABC) = \operatorname{Tr}(BCA)\). Therefore, we get \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial P} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} V^T \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times N}\).

In \(P = \operatorname{softmax}(S)\), as \(\operatorname{softmax}\) is applied row-wise, it is more appropriate to consider the input as each row of \(S\), i.e., \(P_{i, :} = \operatorname{softmax}(S_{i, :})\) when deriving the gradient formula.

\[dL = \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial P_{i, :}} \right)^T dP_{i, :} = \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial P_{i, :}} \right)^T \operatorname{dsoftmax}(dS_{i, :})\]The derivative \(df_x\) of a function \(f\) mapping vectors from \(\mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^n\) is a linear transformation \(df_x \in \mathcal{L}(\mathbb{R}^n, \mathbb{R}^n)\), which can be expressed in its matrix form (Jacobian matrix). The Jocobian matrix (i.e., the derivative) of \(y = \operatorname{softmax}(x)\), where \(x \in \mathbb{R}^n\) is a column vector, is an \(n \times n\) symmetric matrix, \(\operatorname{dsoftmax}=\text{diag}(y) - yy^T=\operatorname{dsoftmax}^T\).

With the above derivation, we can proceed as follows:

\[dL = \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial P_{i, :}} \right)^T \operatorname{dsoftmax}(dS_{i, :}) = \left( \operatorname{dsoftmax}^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial P_{i, :}} \right)^T dS_{i, :} = \left( \operatorname{dsoftmax} \frac{\partial L}{\partial P_{i, :}} \right)^T dS_{i, :}\]Therefore, we arrive at \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial S_{i, :}} = \operatorname{dsoftmax}(\frac{\partial L}{\partial P_{i, :}})\). With a slight abuse of notation, it can be compactly written as \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial S} = \operatorname{dsoftmax}(\frac{\partial L}{\partial P}) \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}\).

By Two Alternative Methods

Next, we will resort to two alternative methods to verify the correctness of our previous derivations. Yet you will find them a bit more cumbersome.

Component-wise

Recall that in multivariable calculus, Let \(U \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n\) and \(V \subseteq \mathbb{R}^m\) be open and \(f:\: U \to \mathbb{R}^m,\: g:\: V \to \mathbb{R}^k\) with \(f(U) \subseteq V\). Let \(f\) be differentiable on \(U\) and \(g\) differentiable on \(V\). Set \(y = f(x)\) and \(z = (g \circ f)(x) = g(y)\). Then the chain rule \((g \circ f)^\prime(x) = g^\prime(y)f^\prime(x)\) can be written in its matrix form:

\[\begin{bmatrix}\frac{\partial z_1}{\partial x_1} & \dots &\frac{\partial z_1}{\partial x_n}\\ \vdots & & \vdots\\ \frac{\partial z_k}{\partial x_1} & \dots &\frac{\partial z_k}{\partial x_n} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}\frac{\partial z_1}{\partial y_1} & \dots &\frac{\partial z_1}{\partial y_m}\\ \vdots & & \vdots\\ \frac{\partial z_k}{\partial y_1} & \dots &\frac{\partial z_k}{\partial y_m} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}\frac{\partial y_1}{\partial x_1} & \dots &\frac{\partial y_1}{\partial x_n}\\ \vdots & & \vdots\\ \frac{\partial y_m}{\partial x_1} & \dots &\frac{\partial y_m}{\partial x_n} \end{bmatrix}\]In the special case where \(g:\: V \to \mathbb{R}\), the matrix form of the chain rule is expressed as follows:

\[\left[\frac{\partial L}{\partial x_1}, \dots, \frac{\partial L}{\partial x_n} \right] = \left[ \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1}, \dots, \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} \right] \begin{bmatrix}\frac{\partial y_1}{\partial x_1} & \dots &\frac{\partial y_1}{\partial x_n}\\ \vdots & & \vdots\\ \frac{\partial y_m}{\partial x_1} & \dots &\frac{\partial y_m}{\partial x_n} \end{bmatrix}\]If written in component-wise form, we arrive at the familiar formula:

\[\frac{\partial L}{\partial x_j} = \sum_{k=1}^m \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_k}\frac{\partial y_k}{\partial x_j}\]To prove \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial V} = P^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times d}\) using the (multivariable) chain rule, as it only works for vectors as inputs, we should consider each column \(V_{:, j}\) seperately, i.e., \(O_{:, j} = P V_{:, j}\). Yet the derived outcomes from such a workaround can be effortlessly transferred to the matrix \(V\), as each column \(V_{:, j}\) shares the same Jacobian matrix \(P\).

As \(O_{kj} = \sum_{m=1}^N P_{km} V_{mj}\), we get \(\frac{\partial O_{kj}}{\partial V_{ij}} = P_{ki}\). Or, it can be read off from the Jacobian matrix \(P\) as the k-th row and i-th column element (\(\frac{\partial O[:, j]_{k}}{\partial V[:, j]_{i}}\)).

Applying the chain rule, we get

\[\frac{\partial L}{\partial V_{ij}} = \sum_{k=1}^N \frac{\partial L}{\partial O_{kj}} \frac{\partial O_{kj}}{\partial V_{ij}} = \sum_{k=1}^N \frac{\partial L}{\partial O_{kj}} P_{ki} = (P^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial O})_{ij}\]Similarly, we can prove \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial P} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} V^T \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times N}\) by treating each row \(P_{i,:}\) independently which shares the same Jacobian matrix \(V^T\) (\(O^T = V^T P^T\)): \(O_{ik} = \sum_{m=1}^N P_{im} V_{mk}\), so \(\frac{\partial O_{ik}}{\partial P_{ij}} = V_{jk}\). Or, it can be read off from the Jacobian matrix \(V^T\) as the k-th row and j-th column element \(V^T_{kj}\) (\(\frac{\partial O[i, :]_{k}}{\partial P[i, :]_{j}}\)).

\[\frac{\partial L}{\partial P_{ij}} = \sum_{k=1}^d \frac{\partial L}{\partial O_{ik}} \frac{\partial O_{ik}}{\partial P_{ij}} = \sum_{k=1}^d \frac{\partial L}{\partial O_{ik}} V_{jk} = \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} V^T \right)_{ij}\]Matrix vectorisation and the Kronecker product

Actually, it is legitimate to directly work with the Jacobian matrix of matrix inputs/outputs, as any linear operator that transforms vectors between finite-dimensional vector spaces can be expressed in its matrix form once the bases for the input and output vector spaces have been selected. The most common way to achieve this involves matrix vectorisation and the Kronecker product.

The vectorization \(\text{vec}(A) \in \mathbb{R}^{mn}\) of any \(m \times n\) matrix \(A \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}\) is defined by simply stacking the columns of \(A\), from left to right, into a column vector \(\text{vec}(A)\). That is, if we denote the \(n\) columns of \(A\) by m-component vectors \(\overrightarrow{a_1}, \overrightarrow{a_2}, \dots, \overrightarrow{a_n} \in \mathbb{R}^m\), then

\[\text{vec}(A) = \text{vec}(\left[ \overrightarrow{a_1}, \overrightarrow{a_2}, \dots, \overrightarrow{a_n} \right]) = \begin{pmatrix} \overrightarrow{a_1}\\ \overrightarrow{a_2}\\ \vdots \\ \overrightarrow{a_n} \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{mn}\]Then, the Kronecker-product identity that plays a key role in the derivation is:

\[(A \otimes B) \text{vec}(C) = \text{vec}(BCA^T)\]where \(A, B, C\) are compactly sized matrices. There are two special cases derived from the above Kronecker-product identity:

\[(I \otimes B) \text{vec}(C) = \text{vec}(BC)\] \[(A \otimes I) \text{vec}(C) = \text{vec}(CA^T )\]Click here to know more

Proof:

To prove \((I \otimes B) \text{vec}(C) = \text{vec}(BC)\), assume \(B \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times m}\) and \(C \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times k}\),

\[BC = B \left[ \overrightarrow{c_1}, \overrightarrow{c_2}, \dots, \overrightarrow{c_k} \right] = \left[ B\overrightarrow{c_1}, B\overrightarrow{c_2}, \dots, B\overrightarrow{c_k} \right]\] \[\text{vec}(BC) = \begin{pmatrix} B\overrightarrow{c_1}\\ B\overrightarrow{c_2}\\ \vdots \\ B\overrightarrow{c_k} \end{pmatrix} = \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} B & & & \\ & B & & \\ & & \ddots & \\ & & & B \end{pmatrix}}_{\left( I \otimes B \right)} \begin{pmatrix} \overrightarrow{c_1}\\ \overrightarrow{c_2}\\ \vdots \\ \overrightarrow{c_k} \end{pmatrix}\]where \(I \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times k}\).

To prove \((A \otimes I) \text{vec}(C) = \text{vec}(CA^T )\), assume \(A \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times k}\) and \(C \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times k}\),

\[CA^T = \left[ \sum_{j=1}^k a_{1j} \overrightarrow{c_j}, \sum_{j=1}^k a_{2j} \overrightarrow{c_j}, \dots, \sum_{j=1}^k a_{nj} \overrightarrow{c_j} \right]\] \[\text{vec}(CA^T) = \begin{pmatrix} \sum_{j=1}^k a_{1j} \overrightarrow{c_j}\\ \sum_{j=1}^k a_{2j} \overrightarrow{c_j}\\ \vdots \\ \sum_{j=1}^k a_{nj} \overrightarrow{c_j} \end{pmatrix} = \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} a_{11}I & a_{12}I & \cdots & a_{1k}I \\ a_{21}I & a_{22}I & \cdots & a_{2k}I \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ a_{n1}I & a_{n2}I & \cdots & a_{nk}I \end{pmatrix}}_{(A \otimes I)} \begin{pmatrix} \overrightarrow{c_1} \\ \overrightarrow{c_2}\\ \vdots \\ \overrightarrow{c_k} \end{pmatrix}\]where \(I \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times m}\).

To prove \((A \otimes B) \text{vec}(C) = \text{vec}(BCA^T)\),

\[\text{vec}(BCA^T) = (I \otimes B) \text{vec}(CA^T) = (I \otimes B)(A \otimes I) \text{vec}(C) = (A \otimes B) \text{vec}(C)\]where we used the property of the Kronecker product \((A \otimes B)(C \otimes D) = (AC \otimes BD)\).

We are now equipped with all the necessary tools to provide a slightly more elegant way to prove gradients involving matrix inputs/outputs than chunking matrices into column vectors as done previously.

To prove \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial V} = P^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times d}\), as \(dO = P dV\), by vectorisation,

\[\text{vec}(dO) = \text{vec}(P dV) = \underbrace{(I \otimes P)}_{\text{Jacobian matrix :}\; \frac{\partial O}{\partial V}} \text{vec}(dV)\]Recall the special case of multivariable chain rule \(z = (g \circ f)(x) = g(y)\) where \(g:\: V \to \mathbb{R}\),

\[\left[\frac{\partial L}{\partial x_1}, \dots, \frac{\partial L}{\partial x_n} \right] = \left[ \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_1}, \dots, \frac{\partial L}{\partial y_m} \right] \begin{bmatrix}\frac{\partial y_1}{\partial x_1} & \dots &\frac{\partial y_1}{\partial x_n}\\ \vdots & & \vdots\\ \frac{\partial y_m}{\partial x_1} & \dots &\frac{\partial y_m}{\partial x_n} \end{bmatrix}\]We get

\[\text{vec}({\frac{\partial L}{\partial V}})^T = \text{vec}({\frac{\partial L}{\partial O}})^T (I \otimes P)\] \[\text{vec}({\frac{\partial L}{\partial V}}) = (I \otimes P)^T \text{vec}({\frac{\partial L}{\partial O}}) = (I \otimes P^T) \text{vec}({\frac{\partial L}{\partial O}}) = \text{vec}(P^T \frac{\partial L}{\partial O}) \quad \text{QED}\]where we used one property of Kronecker-product \((A \otimes B)^T = A^T \otimes B^T\).

Similarly, the proof of \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial P} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial O} V^T \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times N}\) is shown as follows:

\[dO = dP V\] \[\text{vec}(dO) = \text{vec}(dP V) = \underbrace{(V^T \otimes I)}_{\text{Jacobian matrix :}\; \frac{\partial O}{\partial P}} \text{vec}(dP)\] \[\text{vec}({\frac{\partial L}{\partial P}})^T = \text{vec}({\frac{\partial L}{\partial O}})^T (V^T \otimes I)\] \[\text{vec}({\frac{\partial L}{\partial P}}) = (V^T \otimes I)^T \text{vec}({\frac{\partial L}{\partial O}}) = (V \otimes I) \text{vec}({\frac{\partial L}{\partial O}}) = \text{vec}({\frac{\partial L}{\partial O}} V^T) \quad \text{QED}\]It can be seen that using the trick of matrix vectorisation is more conceptually clear than dealing with gradients involving matrices in a component-wise manner. Yet it is still a bit cumbersome compared to techniques in matrix calculus.

Concluding Remarks

While matrix calculus plays a pivotal role in machine learning and large-scale optimisation, the advent of automatic differentiation (AD) engines in modern scientific computing libraries has largely relieved practitioners from the burden of manually computing derivatives of complex structures like matrices and higher-order tensors. Nevertheless, matrix calculus remains a powerful tool, well worthy to be included in your analytical arsenal.

In part 2 of this blog, we will walk through the implementation of the backward pass of FlashAttention in Triton.

Acknowledgement

We express our gratitude to Matrix Calculus (for Machine Learning and Beyond)

@misc{Cai2025flashattnbackward-1,

author = {Xin Cai},

title = {Learning the Backward Pass of FlashAttention: Part I Derivations},

howpublished = {\url{https://totalvariation.github.io/blog/2025/intro-flashattention-backward-part1/}},

note = {Accessed: 2025-07-21},

year = {2025}

}